In a recent publication, Eemeli and collaborators have studied the observability of stiff periods of decelerated expansion in the early history of the universe.

There are reasons to believe the early Universe was dominated by a scalar field which caused space to expand in an accelerating manner. After this Cosmic Inflation, the scalar field was replaced by radiation consisting of Standard Model particles. The subsequent radiation-dominated era is well understood. For example, the nuclei of light elements were born during it through the process of Big Bang Nucleosynthesis (BBN). Theoretical computations of BBN match very well the observed late-time abundances of these elements (with the possible exception of lithium). Hence, by BBN, the Universe must have settled to the standard radiation-dominated behaviour, and any exotic ingredients beyond the Standard Model must have vanished or become negligible. However, the era between inflation and BBN is less constrained, and exotic processes may have taken place there.

It is, in fact, possible that scalar fields may have dominated the Universe for some time even after the end of inflation. This happens in models of quintessential inflation, where the scalar field responsible for inflation sticks around and later comes to play the role of dark energy, causing the Universe to inflate again at late times. Right after the primordial inflation, the scalar field typically undergoes kination, motion dominated by the scalar’s kinetic energy. A long period of kination leaves a mark: it amplifies gravitational waves born during inflation. This has a two-fold effect. First, the amplified gravitational waves may become detectable in future gravitational wave observatories. Second, the gravitational waves may break the delicate balance of BBN, producing wrong ratios of light elements and making the model unviable.

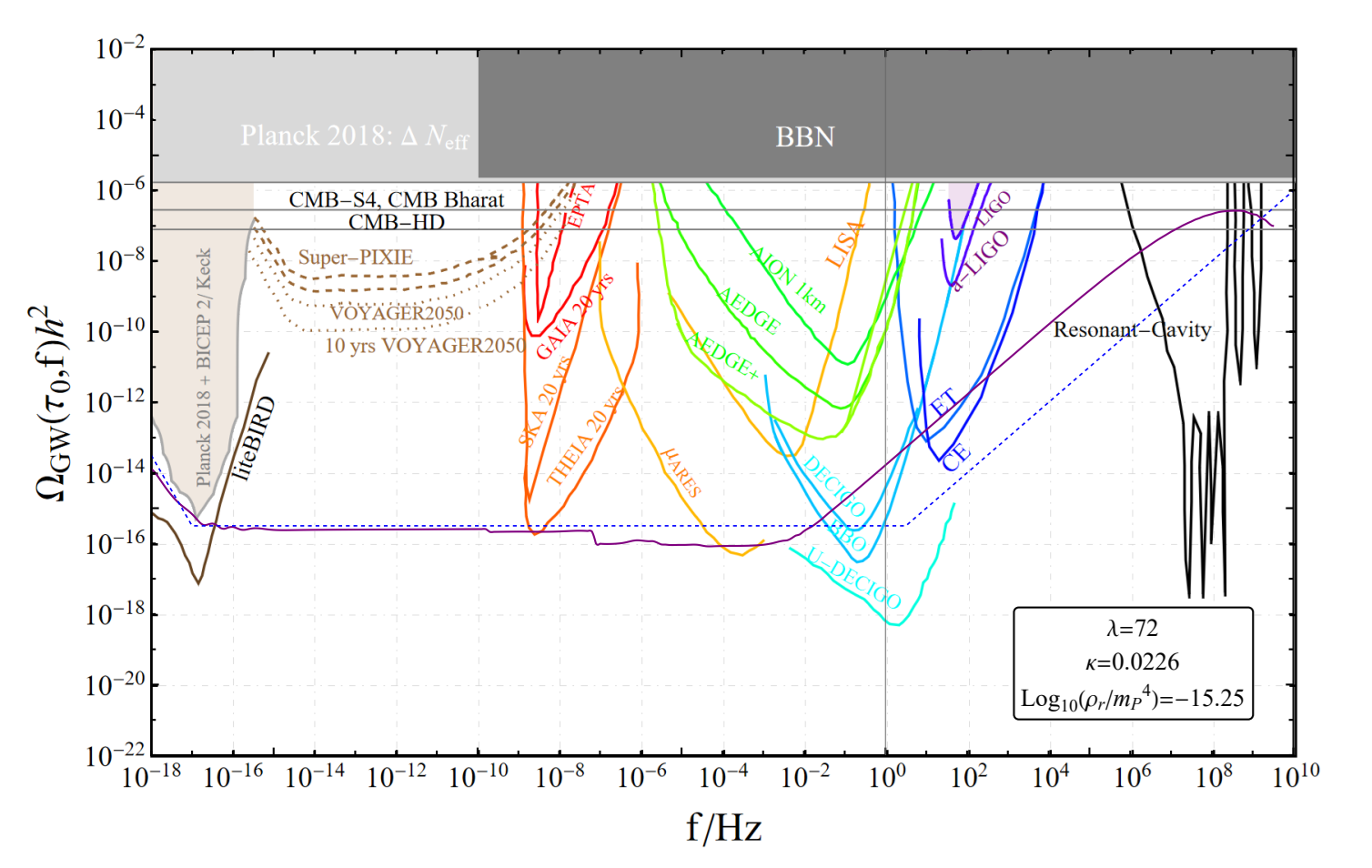

The second effect tends to kick in before the first: observationally interesting models are ruined by their inability to abide by the BBN bound. In Ref. [1], Eemeli worked together with Konstantinos Dimopoulos and Lucy Brissenden from Lancaster University to show that there is a class of kination models that respects the BBN bound but is still detectable by future gravitational wave experiments. The trick is to make the transition from inflation kination (called a ‘stiff’ period) ‘soft,’ so that the Universe’s equation of state changes slowly during this era. The effect on the gravitational wave spectrum is depicted in the following figure:

The colored curves represent the sensitivities of current and future gravitational wave (and other) experiments for various gravitational wave frequencies. BBN sets a universal limit on the gravitational wave spectrum across all frequencies. The semi-vertical lines are two example spectra, one with standard kination (dashed blue) and one with a soft transition period (purple). The standard case increases steeply all the way to the highest frequencies, narrowly avoiding the BBN bound, but also missing most of the gravitational wave detectors’ sensitivities. The soft case has a rounded top (corresponding to the soft period), again avoids the BBN, but this time also hits the sensitivities of the Einstein Telescope (ET) and the Cosmic Explorer (CE). The maximum frequency for both curves is approximately fixed by the energy scale of inflation, which is here set to the highest observationally allowed value, since this also produces the highest gravitational wave density.

The soft period in [1] was produced by a double-exponential scalar potential motivated by string theory. With only a little tuning, the model produces both detectable gravitational waves and the correct dark energy behaviour at late times. The model also satisfies other necessary constraints, such as the requirement for the scalar field itself to be sufficiently suppressed during BBN. It paves the way for other models that can produce similar effects.