Eemeli has studied the formation of primordial black holes from inflationary perturbations together with collaborators from the University of Helsinki.

As discussed in, for example, here, cosmic inflation is an early era during which a scalar field makes the Universe expand extremely fast. Small ripples in the field can get amplified, so that some patches of space end up with more matter than others when inflation ends. If the extra matter is compact enough, it collapses into a primordial black hole. Computing the black hole statistics from a given model of inflation is an active field of study.

Compactness of matter is measured with the compaction function \(\mathcal{C}\), the extra mass \(\Delta M\) in a given patch of space divided by the patch’s radius \(R\). To see if a black hole forms around a given point in space, we can compute the compaction function for many patches of varying radii around the point. These give the radial profile of the compaction function. The profile goes to zero for small and large radii (where \(\Delta M\) becomes small and \(R\) becomes large, respectively), but may have a high peak at intermediate scales. If the peak is high enough, it triggers black hole collapse. The radius at the peak gives the black hole’s mass.

The compaction function is tricky to compute from models of inflation; indeed, usually cosmologists like to work with another perturbation quantity, the curvature perturbation \(\zeta\). The two quantities are related but not identical: the compaction function is related to the curvature perturbation’s radial derivative. It is commonly assumed that a high curvature perturbation corresponds to a high compaction function, so that the curvature perturbation can be used to estimate the abundance of primordial black holes. In Ref. [1], together with Syksy Räsänen and Sami Raatikainen from the University of Helsinki, Eemeli has shown that this is not always the case.

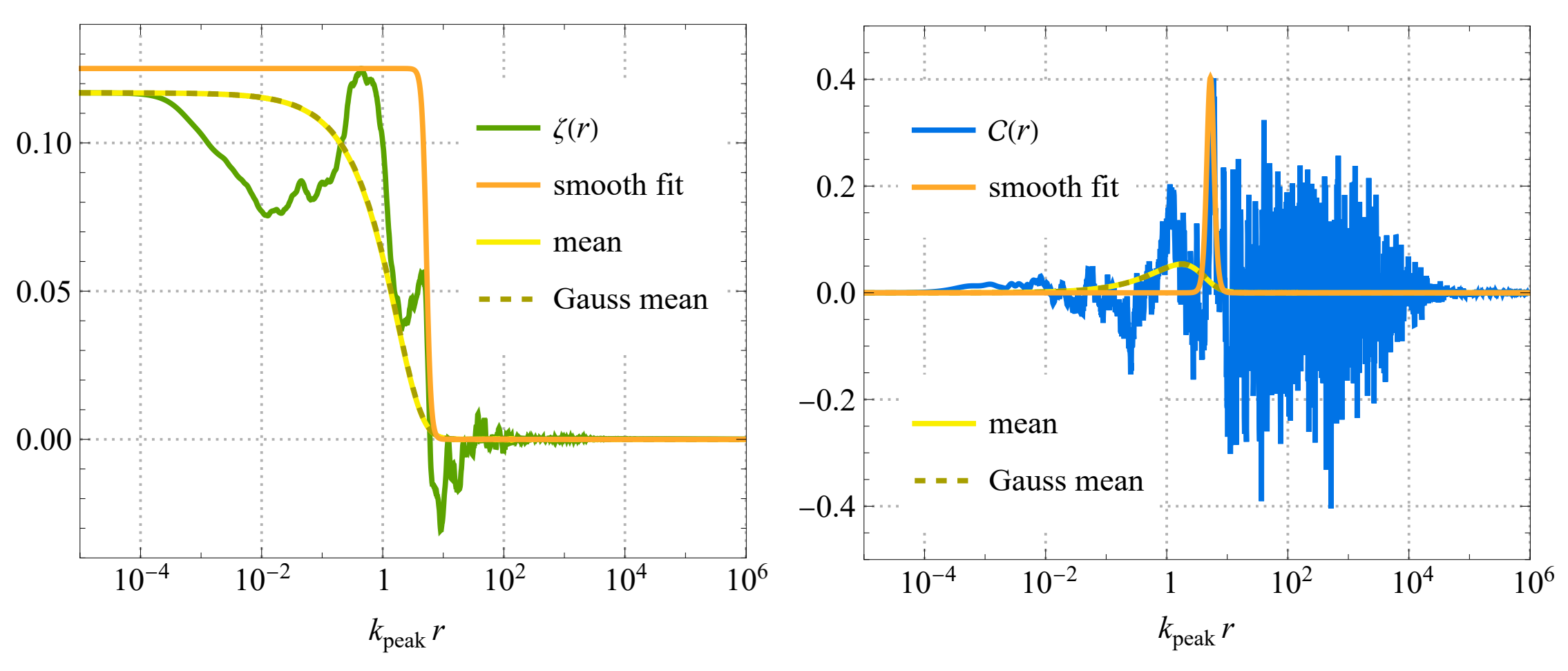

In Ref. [1], the authors performed a numerical study of inflationary perturbations using the method of stochastic inflation (for more on stochastic inflation, see these posts: arXiv:2507.15522, arXiv:2504.17680, and arXiv:2501.05371. With Finnish supercomputers, they built \(10^8\) radial perturbation profiles in three typical single-field primordial black hole models. The study is the first one to construct the full radial profiles; previous studies have been limited to studying the perturbations only at fixed length scales. This was achieved through a Fourier transform of over 10 000 correlated momentum shells, revealing the full correlations between different radii. Interestingly, the compaction profiles turned out to be very spiky, with sharp dips up and down instead of wide, smooth peaks. The figure below shows an example case: on the left, the curvature perturbation profile, and on the right, the corresponding compaction function profile (together with various estimates; for details, see Ref. [1]).

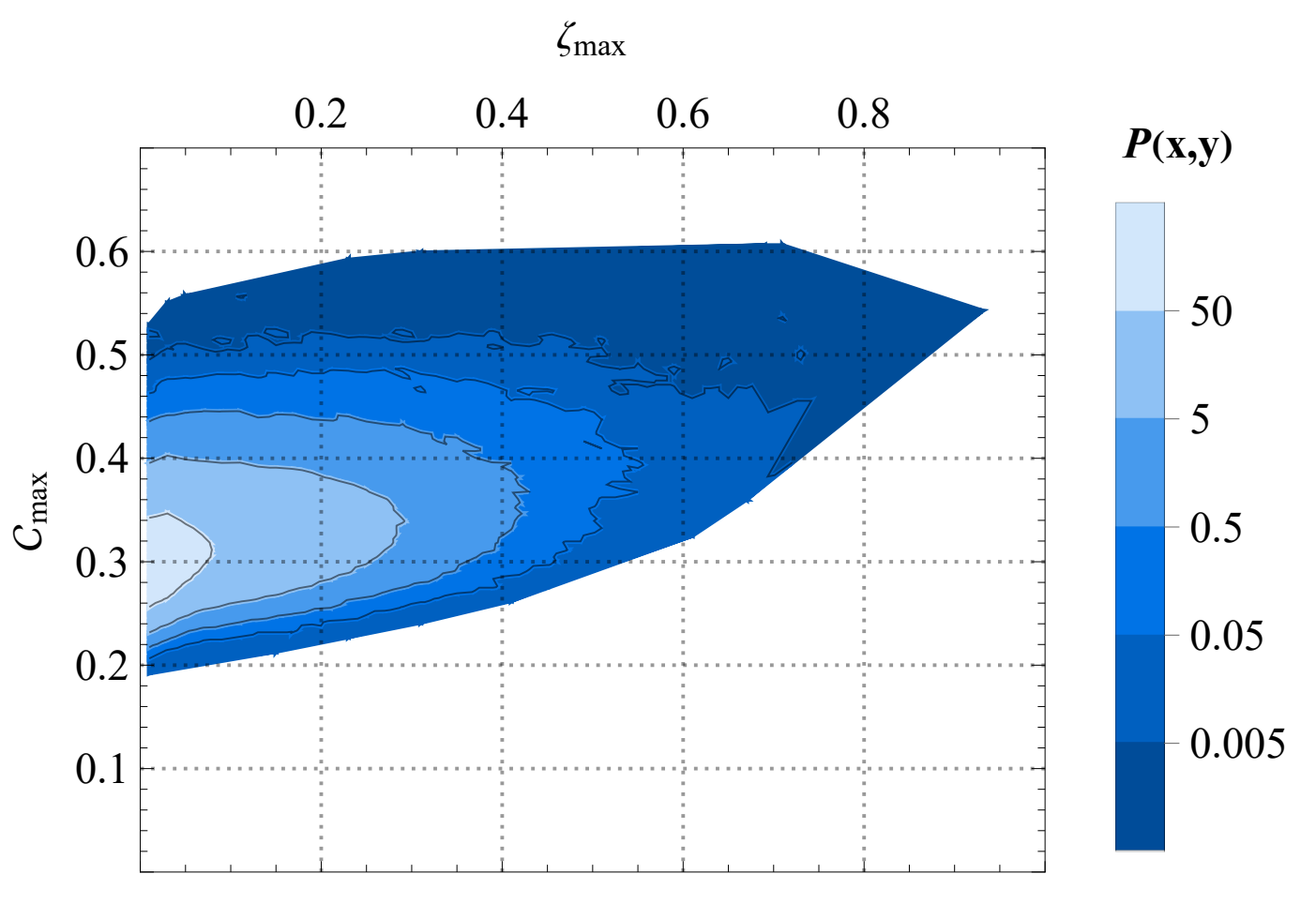

Previous studies have mainly used the curvature perturbation amplitude as a criterion for black hole formation. The statistics of the radial profiles show, however, that the maximum amplitudes of the compaction function and the curvature perturbation are not very strongly correlated, see the figure below:

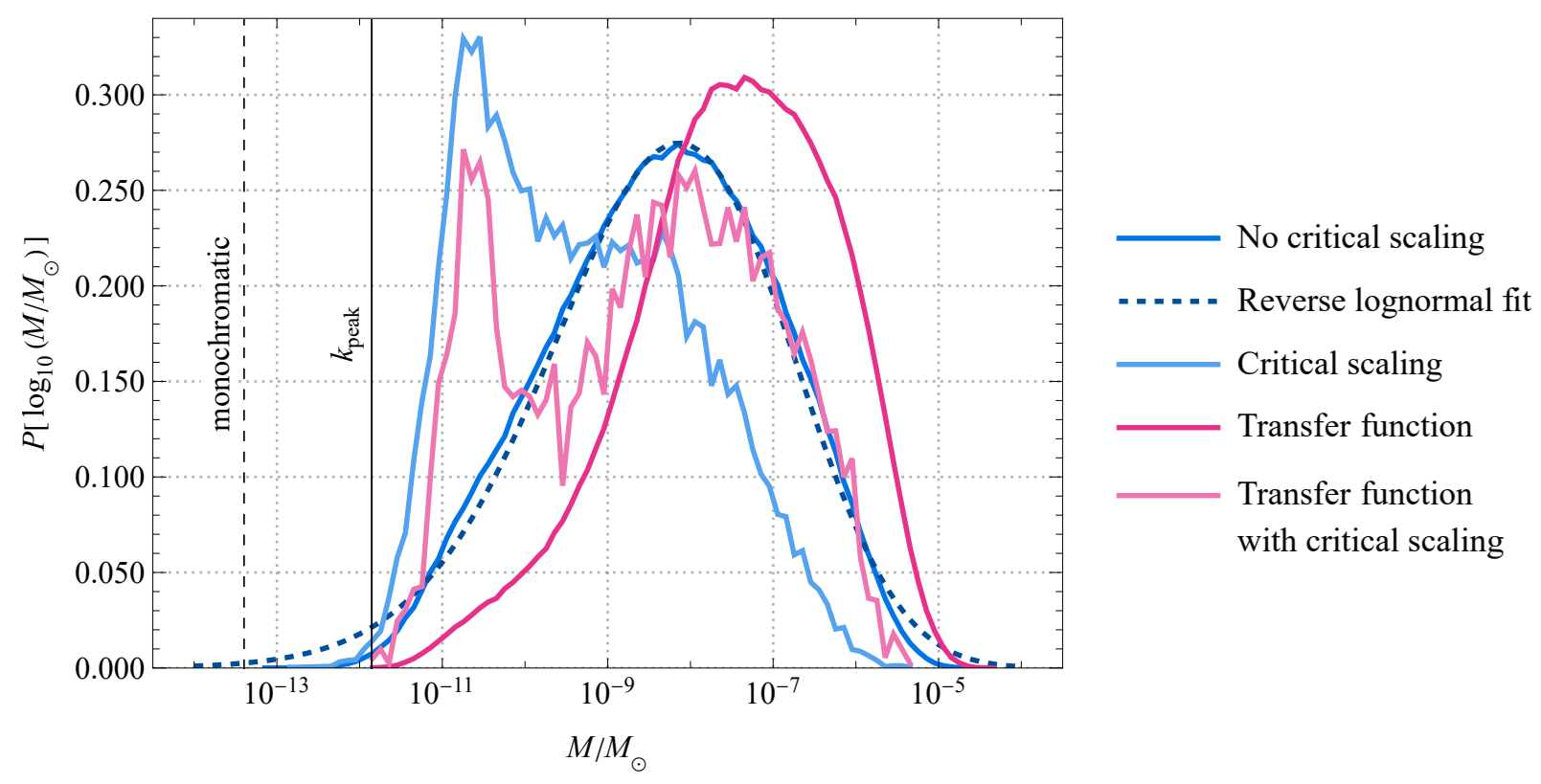

Previous work has argued that black hole abundance is enhanced by non-perturbative effects that modify the curvature perturbation distribution, giving it an exponential tail. The results of [1] indicate that the spikiness of the profiles has an even larger effect on the abundance, increasing it by many orders of magnitude compared to previous estimates. The compaction function spikes rise well over typical mean profiles deduced from the curvature perturbation amplitude, forming black holes even in cases where the curvature perturbation stays small. As a consequence, the curvature perturbation spectrum required to form abundant black holes is smaller than previously assumed, of order 0.001 by a preliminary estimate. Since the spikes can form at many different scales, the black hole mass distribution becomes wide, as shown below. Such a wide distribution may clash with observational constraints.

The results of [1] come with caveats. The collapse threshold used in this work is based on earlier numerical relativity simulations, which consider gravitational collapse starting from smooth profiles. The narrow and spiky compaction function peaks found here are quite different, and new collapse simulations are needed to see how this affects the collapse threshold. The wide mass distributions also suffer from convergence issues, and it is possible that the large-scale peaks get wiped out by cosmological evolution before they have time to collapse into black holes. More work is needed extract all information from the spiky perturbation profiles.